Milan – Church of Santa Maria delle Grazie

The foundation of a second Dominican friars’ settlement in Milan, in addition to the first ancient settlement of Sant’Eustorgio dating back to 1227, dates back to 1459. The congregation of Dominicans, established at the present-day church of San Vittore al Corpo, received a piece of land as a gift from Count Gaspare Vimercati, a mercenary in the service of the Sforza, in 1460. On this land there was a small chapel dedicated to Santa Maria delle Grazie, and a building with a courtyard for Vimercati’s troops. On September 10, 1463, the first stone of the convent complex was laid. The construction began from what is now the Chiostro dei Morti, adjacent to the original chapel of the Virgin of Grace, which today corresponds to the last chapel in the left nave of the church. Guiniforte Solari, the most prominent architect in Milan at that time, who had already been the chief engineer of the Cathedral, the Ospedale Maggiore, and the Certosa di Pavia, was called upon to direct the works. Thanks to Vimercati’s patronage, the convent was completed in 1469.

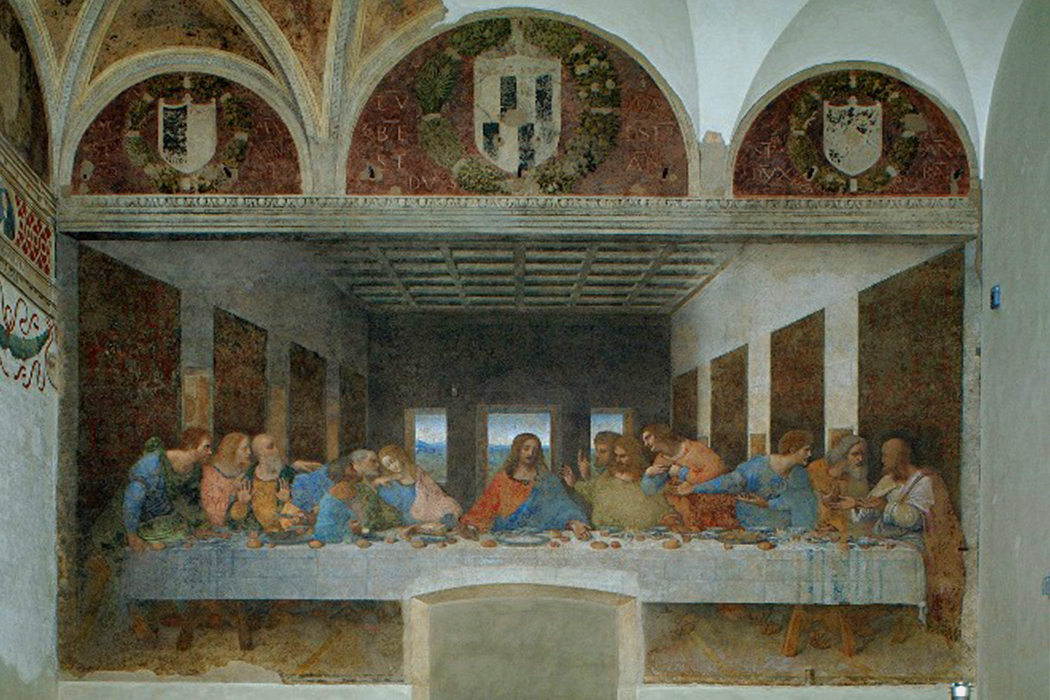

The convent was structured around three cloisters. The original Vimercati troop quarters were incorporated into the building, while the Frati’s cells overlooked the Chiostro Grande, and the Chiostro dei Morti was adjacent to the church. Today, there is a post-war reconstruction of the latter because it was completely destroyed by bombings in 1943. It is constituted, on the north side, by the northern flank of the church, while on the other three sides there is a porch of columns in serizzo with Gothic capitals with smooth leaves. On the porch, to the east, are the ancient Chapel of Grazie, the Chapter and Parlour rooms, and to the north the library, built by Solari on the model of the already famous library of the Dominican convent of San Marco in Florence, designed by Michelozzo twenty years earlier. The southern side is entirely occupied by the refectory, containing the famous Last Supper by Leonardo da Vinci.

The construction of the church began, as usual, from the apse area, at the same time as the construction of the convent. In the project, Solari followed the consolidated Lombard Gothic tradition of the three-naved basilica, with ogival vaults and a gable facade. The materials are also those of the Lombard tradition, with brick for the walls and granite stone for the columns and capitals. The plan is that of the hall church, with three low and wide naves, separated by stone columns that facilitate the passage of light creating a unified environment, developed more horizontally than vertically. The naves are covered with cross-ribbed vaults with cordons, held up by capitals with leaves. The capitals are no longer smooth leaves as was the custom, but with motifs reminiscent of the Corinthian order, which is a timid concession to the classicizing style that was already spreading in the North. The minor naves are flanked by rows of seven square side chapels, illuminated by a central roundel and two pointed arch windows. The structure is therefore the same as the previous Dominican headquarters of Sant’Eustorgio.

The simple gable facade is divided into five compartments by six buttresses. The width is almost double the height, which nevertheless exceeds that of the internal naves, as can be seen from the blind windows placed above the roofline. The sober decoration consists of the relief molded bricks that frame the mullioned windows and the rose windows, and the arches that decorate the cornice.

The central portal, in white marble, is the first intervention carried out at the behest of Ludovico il Moro, who took over the patronage of the complex’s work after Vimercati had become responsible for a failed conspiracy. The attribution of the project, attributed by some to Bramante, is not unanimous. The candor of the white marble, the grace of the classical-inspired decorations, and the geometric linearity of the portal are enhanced by the contrast with the sober brick structure of the facade.

In 1492, the new Lord of Milan, Ludovico il Moro, following the sumptuous wedding with Beatrice d’Este, decided to erect a monument that would bear witness in Milan to the new style now widespread in the richest and most up-to-date courts of the peninsula, such as Florence, Ferrara, Mantua, Urbino, and Venice. Thus, only ten years after Solari completed the church, the choir with two side chapels, which had just been built, was demolished, and on March 29, 1492, Archbishop Guidantonio Arcimboldi blessed the first stone of the new apse.

Traditionally attributed to Bramante, who was the Ducal architect at that time, and who was mentioned once in the Church’s acts (a delivery of marble in 1494), the project is not documented. Recent studies have also mentioned Amadeo’s name. The Bramante was almost undoubtedly responsible for the initial design, but did not follow the actual work, which was probably directed by Giovanni Antonio Amadeo.

According to some scholars, it was Ludovico’s intention to undertake a complete renovation of the church, although only the apsidal part was actually realized. However, Bramante is also credited with other episodes of the late fifteenth-century transformations, such as the old sacristy, the small cloister and perhaps the refectory.

The apse is made up of an imposing cube, at the center of which stands the hemispherical dome, joined by pendentives, in which are inscribed tondi that enclose the Four Doctors of the Church. The dome rests on a low drum, which has the original appearance of a large loggia that runs along the entire circumference, alternating open and blind mullioned windows. The clear geometric figure of the circle of the dome, symbol of perfection, is taken up by the decoration of black circular motifs on white plaster, from the row of open oculi at the top to the central rosette of the lantern. Grand arches in the center occupy the four sides of the cube, whose summits are tangential to the circumference of the dome. The two side arches open onto symmetrical apses, with coffered vaults. The two central arches open onto the central nave and the choir respectively. The latter consists of a cubic space with an elegant umbrella vault, ending in an apse identical to the previous ones. The general structure recalls the layout of the Brunelleschi Sacristy in San Lorenzo in Florence, and the Portinari Chapel in Sant’Eustorgio. Circular motifs of the tondi are repeated throughout the decoration, inscribed in the high frieze, the sub-arches, the pendentives, and the dome, as well as the motif of the radiating wheel, already used by Bramante in the Prevedari engraving and in Santa Maria near San Satiro.

On the outside, the apse appears as a monumental cube, from which the two semicircular apses depart from the sides, while behind there is the parallelepiped of the choir, which also concludes with a semicircular apse identical to the two lateral ones. Above, the dome is enclosed in a dome-shaped lantern that rises up in the form of a sixteen-sided prism, ending in the high gallery. On the north side is the small bell tower, rectangular in plan, which rises alongside the dome up to the height of the gallery. The decoration, which, along with the Certosa di Pavia and the Colleoni Chapel, is one of the best examples of plastic decoration in the Lombard Renaissance scene, is made of terracotta, granite, and Angera stone. The tall granite pedestal with cornices features large circular patères with Sforza and Dominican coats of arms. On the upper band, a series of windows and niches with terracotta frames runs. Above, a high plastered part shows more elaborate decoration. Tondi with elegant geometric patterns alternate with Corinthian terracotta pilasters and classic-looking chandeliers. On the squares that make up the pedestals for the pilasters, floral decorations alternate with medallions with busts of saints. The decoration of the lantern of the dome is also particularly redundant. A series of rectangular mullioned windows crowned with a tympanum is surmounted by bands of terracotta decorations, and finally the high gallery supported by columns and arches, behind which the oculi that provide light inside.

It is not clear whether the intention of the Moro to make the Chiesa delle Grazie the burial place of the Sforza was present from the beginning, or whether it matured only in 1497, after the death of the beloved consort Beatrice d’Este from the consequences of a premature birth. The Duchess, who died at the age of only twenty-two, was buried with great honors inside the choir of the basilica. The isolated funerary monument, not attached to the wall, was made of white marble by Cristoforo Solari, with the representation of both spouses lying life-size on the top. Following the death and burial of the Moro in France, at the end of the captivity to which he was forced after the defeat of Novara, and in obedience to the dictates of the Council of Trent, in 1564 the monument was dismantled and dispersed for sale. Only the cover with the statues of the Dukes was subsequently placed inside the Certosa of Pavia.

Today in the choir it is possible to admire the wooden benches intended for the friars. The benches are arranged in two rows. The tarsias of the lower row show a more archaic style, with a prevalence of geometric motifs. The dorsal panels of the upper row feature highly refined tarsias depicting figures of saints alternating with floral motifs, created in the early sixteenth century.

According to an ancient Milanese tradition, Ludovico il Moro also built a tunnel connecting the castle, later named the Sforza Castle, to the convent.

The Pietro Maschera hall, rectangular in shape, has sides of 4×1 and a length of 35.5 m, covered by a lunette barrel vault, which ends in the end walls with umbrella vaults. The construction of the refectory was begun around 1467 and completed around 1488, including the flooring, plastering and furnishings. The project proved to be remarkable, having to cover a large, vaulted space without columns or pillars. In fact, some static problems immediately arose, leading to the reinforcement of the western wall with iron tie rods, in contrast to the opposite wall, balanced by the thrusts of the portico on the Chiostro dei Morti. On the wall facing the Chiostro dei Morti, a barrel vault was to have eight windows corresponding to the lunettes. The windows underwent numerous modifications over time: the western ones were enlarged in the post-war period, while those on the Chiostro dei Morti were bricked up by Luca Beltrami during the early 1900s restorations. Some windows were also modified after the establishment of the Inquisition in the complex.

With the fall of Ludovico il Moro (1499), and the subsequent transfer of the Duchy of Milan to the Spanish Crown after the extinction of the Sforza dynasty (1535), all construction works, which had had Duke Ludovico as their main promoter and financier, ceased. Pictorial decoration continued throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

The Inquisition, existing in Milan from the mid-13th century, with its headquarters at the Dominican convent of Sant’Eustorgio, was moved to the convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie in 1558, a year of intense anti-Lutheran repression. This happened at the initiative of the Dominican Michele Ghislieri (Supreme Inquisitor and future Pope Pius V) and Ippolito Beccaria, the general of the Dominicans, who from 1588 built the new Ecclesiastical Tribunal next to the convent, a genuine Palace of the Inquisition, with a monumental entrance, a prison tower, an apothecary, rooms for meetings and the archive. In 1775, Maria Theresa of Austria established that the inquisitors would no longer be replaced at the end of their term, so the death of the inquisitor Giovanni Francesco Cremona in 1779 definitively marked the end of the Inquisition in Milan.

Remarkable were the works sent to France during the Napoleonic spoliations. The church housed Tiziano’s Crowning with Thorns, which was requisitioned during the French occupation of Lombardy and taken to the Musée Napoleon. Gaudenzio Ferrari’s St. Paul in Meditation was taken to the Museum of Lyon where it still is today. After the Congress of Vienna, the Austrian government did not request its return to the Louvre.

On May 7, 1799, the convent was suppressed, becoming a military barracks, while outside, the Cloister of Frogs and the Bramante Tribune ended up covered with popular constructions. The complex was only recovered in 1860 with a major intervention under the direction of Luca Beltrami, which saw the opening of Via Caradosso and work carried on from the end of the 19th century until 1937. Inside the church, under the completely removed repainting and decoration, the original 15th-century fresco decorations of the nave were rediscovered, as well as the scratch decorations of the Tribune. Outside, the apse was freed from the constructions that were leaning against it, and the bell tower was rebuilt in the style of the Tribune, lowering its height. Also in Renaissance Revival style, the small Cloister of the Prior was built, accessed from the Cloister of Frogs.

In 1924, the convent was returned to the Dominicans, and on the night of August 15, 1943, Anglo-American bombers hit the church and the convent. In these bombings, the Cloister of Frogs was hit by some incendiary bombs, whose flames were quickly thwarted by the friars.

During the world wars, the painted walls of the refectory were protected by a double layer of steel pipes with thick sandbags, which allowed them to be safeguarded from the strong damage of the bombings. The eastern wall and part of the porch were instead destroyed and, from 1945, rebuilt. However, the bomb damage and post-war work brought critical issues to the statics of the structure, including the Cenacle, since the structure between the refectory and the library had been lost. Also for this reason, in the second half of the 20th century, the painting was subject to numerous restorations, to which in 1995 an air filtration system was added to safeguard it.